In 1930, prospector Harold Lasseter claimed he had found a rich gold-bearing quartz reef somewhere in the remote heart of central Australia. He described a deposit so valuable it could change fortunes, yet its location remained vague and unverified.

To this day, no one has confirmed the existence of what became known as Lasseter’s Reef.

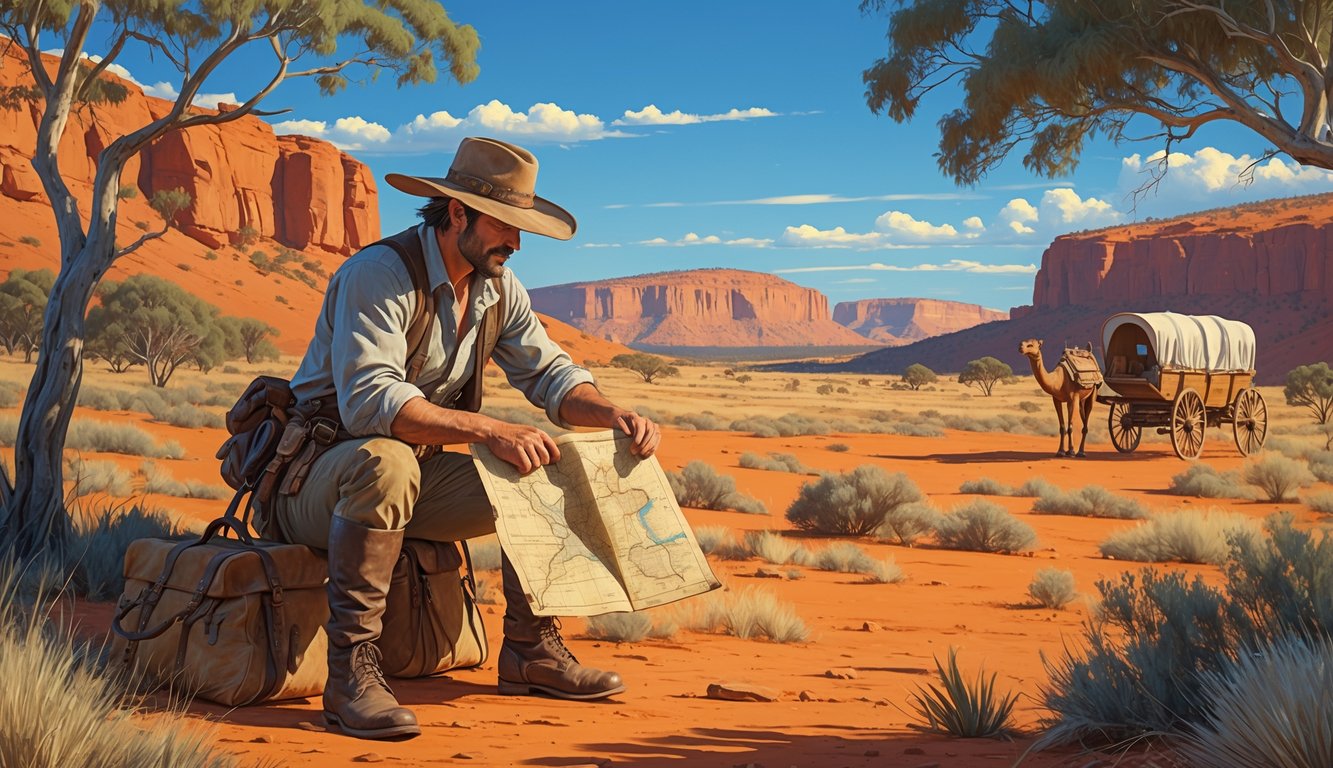

The legend has drawn explorers, adventurers, and fortune seekers into the harsh Australian outback for nearly a century. Many have tried to retrace Lasseter’s steps through deserts, rocky ranges, and isolated landmarks.

Each attempt brings new details and theories about whether the reef is real or just a story that grew over time. The mystery continues to spark debates.

This journey into Lasseter’s Gold explores the man behind the claim and the expeditions that followed. It also examines the lasting impact the tale has had on Australian culture.

The geography of the outback shaped the search, and controversies fuel skepticism. The mystery still inspires people to keep looking.

The Legend of Lasseter’s Gold

In 1930, Harold Lasseter said he had once found a massive gold-bearing quartz reef in Central Australia. His story led to expeditions and debate that still draw interest nearly a century later.

Origins of the Story

Harold Lasseter first spoke of the reef in 1929, claiming he had discovered it in 1911 while traveling alone. He described a rich deposit of gold in a remote desert area.

He gave a vague location, somewhere west of the MacDonnell Ranges. This made it hard for others to verify his story.

In 1930, Lasseter joined a government-backed expedition to find the reef. The journey faced harsh desert conditions, mechanical failures, and disagreements among team members.

Lasseter eventually continued alone with camels. His diary records his struggle to survive and his belief he was close to the gold.

He died in early 1931. No one found confirmed evidence of the reef.

The Myth and Its Impact

The tale of Lasseter’s Reef became one of Australia’s most enduring gold legends. Some believed it was a real but lost discovery, while others thought it was a fabrication.

Over time, the story inspired prospectors, adventurers, and even filmmakers. Documentaries such as Lasseter’s Bones explored both the mystery and Lasseter’s life.

The legend influenced local culture. In Alice Springs, a casino was named after Lasseter, showing how the myth became part of the region’s identity.

Many expeditions have searched for the reef, but none have produced proof of its existence. The idea of hidden gold in the outback remains compelling.

Public Fascination

Public interest in Lasseter’s gold has lasted for decades. The mystery combines adventure, survival, and the lure of untapped wealth.

Media coverage, books, and films keep the story alive. Conflicting accounts in Lasseter’s own writings add to the intrigue.

For some, the search is about more than gold. It represents the challenge of the Australian interior and the idea of discovery.

Even today, explorers still venture into Central Australia hoping to find Lasseter’s Reef. The legend continues to call those seeking fortune or the satisfaction of solving a mystery.

Harold Lasseter: The Man Behind the Mystery

Harold Bell Lasseter was an Australian prospector whose story became one of the country’s most enduring legends. His life combined hardship, bold claims, and a tragic end in the desert.

The details of his background and the disputes over his account continue to shape how people view his legacy.

Early Life and Background

Harold Lasseter was born on 27 September 1880 in country New South Wales. His early years involved frequent moves, and he worked in trades such as laboring and camel driving.

He developed bush skills that later helped him survive in remote areas. These skills included navigation, horsemanship, and basic survival techniques.

By his mid-20s, Lasseter had traveled widely across Australia. He claimed to have first found a rich gold reef during one of these journeys in central Australia.

However, he said he could not relocate it at the time due to harsh conditions and lack of supplies. His life before the famous expedition was not well documented, so historians rely on scattered records and personal accounts.

Motivations and Personality

Lasseter wanted to return to the desert because he believed the gold reef he had once seen could change his fortunes. In the late 1920s, he sought financial backing for an expedition to find it again.

Friends and associates described him as determined and resourceful. He was known to be private about certain details, especially the exact location of the reef.

His diary, later known as Lasseter’s Diary, revealed both optimism and frustration during the 1930–1931 expedition. He wrote about the physical hardships, the challenges with his team, and his strong belief in the reef’s existence.

Many saw him as a man who valued persistence, even when the risks were high.

Controversies and Conflicting Accounts

People have long debated Lasseter’s story. Some believe he genuinely found a gold-bearing reef, while others think he exaggerated or invented the claim.

During the 1930–1931 expedition, Lasseter disagreed with expedition leaders and had trouble with navigation. Cooperation broke down, and he set off alone with camels into the desert.

He died in early 1931, likely from starvation or dehydration. A patrol later found his body.

No one has confirmed the location of the reef he described, often called Lasseter’s Reef. Different versions of his final days and questions about his diary entries have fueled the mystery for nearly a century.

Discovery Claims and Early Expeditions

Harold Bell Lasseter’s story centers on a supposed gold reef in one of the most remote parts of central Australia. His claims led to expeditions, partnerships, and rescues that remain part of Australian outback history.

Key figures and events shaped how the tale developed and why people still discuss it today.

Initial Gold Reef Discovery

Lasseter claimed he first saw the gold deposit in 1897 while traveling through Central Australia. He described a long quartz reef rich in gold.

He said he was on horseback when he came across the site. He did not have the tools or resources to extract any gold at the time.

Years later, in 1929, he repeated his story publicly. Prospectors and investors became interested.

Some viewed his claims as credible, while others doubted the existence of such a rich gold reef. The location he described was vague, and he gave few details, making it hard for others to retrace his path.

Joseph Harding’s Role

Joseph Harding, a prospector and bushman, became one of Lasseter’s early associates. He helped organize supplies and routes for the expedition.

Harding also worked to secure financial backing for the journey. Some records suggest Harding questioned Lasseter’s directions and found inconsistencies in the distances and landmarks described.

Despite doubts, Harding stayed involved. His experience in the outback helped with navigation and planning search strategies for the alleged gold deposit.

The Afghan Camel Driver

Lasseter’s story included a rescue by an Afghan camel driver after his horse died in the desert. The man found Lasseter dehydrated and near collapse.

The driver nursed him back to health and helped him reach safety. This part of the story shows the important role Afghan cameleers played in remote Australian travel during that era.

Afghan camel drivers were skilled in desert navigation and could carry heavy loads over long distances. Their camels were essential for crossing arid regions where horses often failed.

This rescue became a key part of the Lasseter legend and added a human connection to the solitary gold reef claim.

Conflicting Timelines

One challenge in verifying Lasseter’s account is the inconsistency in his reported dates. He sometimes stated he found the reef in 1897, but other times suggested it was years later.

Historians and researchers have noted these contradictions. They make it harder to confirm whether the events happened as described.

Some suggest Lasseter may have confused details over time, while others believe he changed the timeline on purpose. The uncertainty over when he discovered the reef adds to the mystery and has fueled debate among those still searching for Lasseter’s Reef.

The 1930 Central Australian Gold Exploration Expedition

In early 1930, a well-organized team set out from Alice Springs to look for the gold reef Harold Bell Lasseter claimed to have found. Investors backed the expedition, and experienced bushmen led it.

The team brought vehicles, camels, and supplies for months in the desert.

Planning and Funding

The Central Australian Gold Exploration Company Ltd. organized the mission. Its goal was to verify Lasseter’s claim of a rich gold reef in remote Central Australia.

Private investors and company shareholders provided funding. They paid for motor trucks, camels, rations, and survey equipment.

Organizers combined modern transport with traditional desert travel methods. Trucks carried heavy loads where possible, while camels handled rougher country.

The plan relied on Lasseter’s memory of a trip he said he made in 1897 or 1911. Maps were vague, so much of the route depended on his descriptions.

Key Members of the Expedition

Fred Blakeley led the expedition for his bush experience and ability to manage men in harsh conditions.

George Sutherland, a surveyor, mapped and recorded the route. His skills were crucial for navigation in largely uncharted territory.

Phil Taylor served as mechanic and kept the motor trucks running in extreme heat and dust.

Errol Coote, a pilot, joined to provide aerial reconnaissance. Aircraft use was limited by weather and landing sites.

Paul Johns managed the camel team, making sure the animals were fed, watered, and ready for long desert hauls.

Lasseter acted as both guide and the reason for the trip. Tensions with other members grew as the journey went on.

Journey from Alice Springs

The expedition began in Alice Springs, the last major supply point before heading west.

Motor trucks carried bulk supplies along the first stretch, following rough tracks and dry riverbeds. When the ground became too soft or rocky, the team transferred loads to camels.

They passed through sparse settlements and Aboriginal lands, often relying on local knowledge for water sources.

Progress was slow. Mechanical breakdowns and difficult terrain forced frequent stops.

Despite these problems, the team stayed determined to push deeper into the desert.

Challenges and Setbacks

Mechanical failures often stopped the motor trucks. Phil Taylor repaired them in extreme heat.

Spare parts were scarce, so the team had to improvise.

Water scarcity threatened the group. Sometimes, they went days without finding a reliable water source.

Tensions increased between Fred Blakeley and Lasseter. They disagreed over navigation and decisions.

The harsh desert climate caused health problems, like dehydration and heat exhaustion. Dwindling supplies slowed progress and made morale worse.

For more background on the expedition’s origins and events, see the State Library of New South Wales account of the second expedition.

Landmarks and Geography of the Search

Explorers searching for Lasseter’s Reef traveled through remote deserts, rugged mountains, and long stretches of plains. These areas cover parts of the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

Extreme heat, scarce water, and long distances make travel difficult in this region.

MacDonnell Ranges and Mount Leisler

The MacDonnell Ranges run east to west through Central Australia. Their red rock ridges and gorges stand out as natural barriers and navigation points.

Expeditions used the ranges as guides when heading into the desert interior.

Mount Leisler sits west of the MacDonnell Ranges in a remote part of the Northern Territory. Explorers named it after Louis Leisler, and it became a key waypoint for early prospectors.

Travel between the MacDonnell Ranges and Mount Leisler meant crossing open desert. Waterholes were rare, so explorers had to plan routes carefully.

Today, roads reach parts of the MacDonnell Ranges, but Mount Leisler remains hard to access. Travelers need off-road vehicles and good preparation.

Petermann and Mann Ranges

The Petermann Range follows the border between the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Its rugged peaks rise sharply from the desert, making travel tough.

Nearby, the Mann Range lies further south and also crosses the state border. Both ranges hold cultural and historical significance for Indigenous people.

For gold seekers, these ranges promised opportunity but brought hardship. Their rocky terrain slowed travel and made carrying supplies more difficult.

Today, the Petermann and Mann Ranges are still remote. Access is limited, and travelers often need permits due to cultural and environmental protections.

Mount Marjorie

Mount Marjorie is a lesser-known landmark in Lasseter’s story. It sits in the western part of the Northern Territory, near the Western Australia border.

Its location made it a reference point for expeditions moving between the Petermann Range and other desert features.

Although not as tall or dramatic as other peaks, Mount Marjorie stands out in the flat desert. Its isolation means expeditions had to carry extra water and fuel, as there were no nearby settlements or reliable water sources.

Key Locations in Central Australia

Central Australia covers a vast area with deserts, mountains, and dry riverbeds. Key places in Lasseter’s story include Lasseter’s Cave near the Petermann Range, where he reportedly sheltered.

The region’s geography is harsh, with hot days, cold nights, and little rain. Travel routes often follow old stock tracks or unsealed roads like the Great Central Road.

Many sites, such as the MacDonnell and Petermann Ranges, now attract adventurers and travelers following the legend of Lasseter’s Reef. The gold’s exact location remains unknown.

Lasseter’s Final Journey and Disappearance

In early 1931, Harold Lasseter searched for his claimed gold reef. Harsh desert conditions, dwindling supplies, and strained team relationships left him isolated in Central Australia.

Separation from the Expedition

Lasseter joined a motorized expedition to find the gold reef he said he had seen years before. The group faced mechanical failures and extreme heat.

Tensions grew over navigation and slow progress. Lasseter wanted to continue west, but others doubted his directions.

Lasseter eventually left the main party with minimal supplies and a few camels. This choice left him exposed to the desert’s heat, scarce water, and long distances between waterholes.

Paul Johns and the Camels

After leaving the main group, Lasseter traveled with Paul Johns, a bushman and camel handler. Johns knew the outback well and guided their small caravan through remote areas.

The men covered long distances, but the camels weakened as food and water ran low. Johns worried about Lasseter’s health and his determination to go deeper into the desert.

When Lasseter became too ill to travel, Johns left him in a shelter with supplies and went for help. Johns took the camels and headed to the nearest settlement. Rescuers could not reach Lasseter in time, as he had moved on alone.

Search and Discovery of Lasseter’s Remains

Months later, prospector Bob Buck searched for Lasseter. He followed clues from Lasseter’s buried letters and camp remains.

Buck eventually found Lasseter’s body near the Petermann Ranges. Lasseter’s diary, later published in Lasseter’s Last Ride, described his struggle with hunger, thirst, and loneliness.

The diary mentioned his regret over the journey’s hardships and his longing for simple food. The gold reef’s location remained unclear, and his notes gave no exact coordinates.

Aftermath and Ongoing Searches

After Harold Lasseter’s death in 1931, his story inspired explorers, prospectors, and adventurers. Many hoped to find the rich gold reef hidden in Central Australia’s remote deserts.

Subsequent Expeditions

Several expeditions set out after Lasseter’s death to find the supposed reef. Some had private investors, while others were small prospecting groups.

During the Great Depression, more people tried gold prospecting for survival. Places like Kalgoorlie sent experienced miners into the desert.

Most expeditions struggled with heat, scarce water, and tough navigation. Many returned without success, reporting only vague landmarks or conflicting details of Lasseter’s route.

A few groups claimed to find traces of quartz or gold, but no one confirmed the reef’s existence.

Modern Search Efforts

Interest in Lasseter’s Reef continues today. Both amateur and professional explorers still search for it.

Some prospectors study archival maps, Lasseter’s letters, and diaries to retrace his path. Others interview descendants of early searchers for new clues.

Media coverage, including documentaries and articles, keeps the story alive. For example, the search continues for Lasseter’s elusive gold reef, with some claiming to have found possible landmarks.

No verified discovery has been made, but the legend still attracts new searchers.

Technological Advances in Exploration

Today’s explorers use tools early expeditions never had. Satellite imagery helps them scan large areas for geological features.

Ground-penetrating radar and metal detectors reveal mineral deposits below the surface. GPS mapping helps explorers stay on course in the outback.

Some teams use drone surveys to photograph hard-to-reach terrain. Others combine historic data with modern geology to focus their search.

These advances improve safety and efficiency, but the area’s remoteness remains a barrier. The reef, if it exists, is still hidden after nearly a century of searching.

Lasseter’s Reef in Popular Culture

The story of Lasseter’s Reef appears in books, films, and documentaries. Writers and filmmakers use the legend to explore themes of persistence, mystery, and the Australian outback.

Books and Documentaries

Authors and filmmakers have examined the tale through research and personal journeys. Some works focus on retracing Lasseter’s path, while others question whether the reef ever existed.

Documentaries often include interviews with historians, old photos, and footage of the Central Australian desert. These show the harsh environment Lasseter faced and the difficulty of finding any gold reef.

Notable examples include Australian Geographic’s exploration of the mystery and ABC News coverage of modern claims to have found landmarks from Lasseter’s account.

Ion Idriess’s Account

Author Ion Idriess helped popularise the legend with his 1931 book Lasseter’s Last Ride. He based it on Lasseter’s diary and reports from the 1930 expedition.

The book mixes facts with a story style that made the tale accessible to many readers. Idriess described the journey, Lasseter’s difficulties, and his final days.

Lasseter’s Last Ride became a bestseller and is still one of the most famous accounts of the legend. It shaped how Australians view Lasseter’s life and his claim of a gold reef.

Lasseter’s Influence on Australian Folklore

Lasseter’s Reef has become part of Australian folklore. The story is told alongside other outback legends, mixing fact and speculation.

It inspired films like Phantom Gold (1936) and influenced place names such as Lasseter’s Casino in Alice Springs. These references keep the legend alive in tourism and local culture.

Folklore versions focus more on Lasseter’s determination and the harsh desert than on the gold itself. This focus helps the story endure, even without proof of the reef.

Controversies and Skepticism

Many people question whether Harold Bell Lasseter truly found a rich gold deposit in the outback. After his death, doubts grew as records, maps, and witness accounts often conflicted.

Some believe the story mixes truth and fiction, while others think it was a complete hoax.

Authenticity of Lasseter’s Claims

Lasseter claimed he had discovered a massive gold-bearing quartz reef decades before his 1930 expedition. He recorded the location in Lasseter’s diary, but his notes were vague and often inconsistent.

During the 1930 journey, his companions began to suspect he was misleading them. Australian Geographic reports that he gave imprecise directions and avoided sharing exact coordinates.

Some historians argue that a gold deposit of that size would have been rediscovered by now. The lack of physical evidence fuels skepticism.

Lasseter’s own accounts changed over time, making it harder to separate fact from fiction.

Conflicting Evidence

Reports from the 1930 expedition highlight major inconsistencies. Lasseter said he had seen the reef in his youth, but the distances and landmarks he described did not match known geography.

Explorersweb’s account describes how expedition members suspected fraud after weeks of fruitless searching. They noticed his reluctance to share details and his tendency to backtrack on earlier statements.

Physical searches over the decades have found no confirmed trace of the reef. Aerial surveys, geological studies, and modern prospecting technology have failed to locate any gold-rich quartz matching Lasseter’s description.

Theories and Debates

Several theories try to explain the mystery:

| Theory | Key Idea | Main Supporters |

|---|---|---|

| True but Lost | Lasseter found gold, but extreme conditions hid it forever | Some geologists, adventurers |

| Exaggeration | He saw gold but overstated its size and value | Skeptical historians |

| Complete Hoax | No gold existed; it was a scheme for funding | Certain researchers, journalists |

Documentary makers, such as those behind Lasseter’s Bones, have explored the idea that others, like Olof Johanson, also knew the location. No verifiable proof has surfaced.

Legacy of Lasseter’s Gold in the Australian Outback

The story of Lasseter’s Reef has left a clear mark on Australia’s remote regions. It has shaped the ambitions of gold prospectors and boosted tourism in places like Alice Springs.

Impact on Modern Prospectors

Many modern gold prospectors still head into the Central and Western deserts hoping to find what Harold Bell Lasseter claimed to have seen. Some use advanced GPS mapping, satellite images, and metal detectors to search more effectively than in the 1930s.

The harsh environment remains the biggest challenge. Extreme heat, scarce water, and vast distances make expeditions risky and costly.

While no confirmed reef has been found, prospectors sometimes uncover smaller gold deposits. These finds keep interest alive and encourage more searches.

The legend has inspired prospecting clubs and guided expeditions. Participants learn survival skills while exploring potential gold-bearing areas.

Tourism and Local Lore

Alice Springs has embraced the Lasseter story as part of its identity. Visitors can see exhibits, photographs, and maps that trace Lasseter’s final journey.

Some hotels, like Lasseter’s Casino, even bear his name. Tour operators offer trips to regions linked to the legend, combining outback scenery with historical storytelling.

This mix of adventure and history appeals to travelers interested in both exploration and culture. Local businesses often use the tale in marketing, from souvenirs featuring gold-themed designs to guided “lost reef” tours.

These activities help keep the story in public memory and support the local economy.

The Enduring Mystery

Lasseter first claimed to have found a rich gold reef in 1929. No one has verified his claim.

His vague directions and the lack of physical evidence have fueled debate for decades. Some historians believe the reef never existed and suggest Lasseter may have been mistaken or misleading.

Others argue that the gold could still lie hidden in a remote, hard-to-reach location. The mystery of Lasseter’s Reef continues to inspire documentaries and books.